My first foray into video posts!

My first foray into video posts!

So my plan today was to write a post about thoughts and conversations I’ve had recently on the subject of failure. The more I wrote and thought and wrote, however, the more I realized that this was bigger than the planned post. So, rather than abandon the post altogether, I’m posting my preliminary plan, with an appeal for your input.

It’s a little overwhelming just how many people have said something about failure. Arianna Huffington said that the “failure is not the opposite of success, it’s part of the process.” Michael Jordan said “I’ve failed over and over again… that’s why I succeed.” A simple Google search reveals countless famous failures, from Albert Einstein to Steve Jobs to Oprah Winfrey. And of course, when all else fails, we fall back on the old saw, “if at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.” We seem to understand that failure is an inevitable part of life. In fact, we collectively resent anyone who appears to be an “overnight success,” feeling like anyone who hasn’t paid their dues hasn’t really earned their fame and fortune.

Yet, when it comes to failure in the academic context, we have a different understanding, a different regard for the student who fails a test, a course, or a grade. There seems to be a lot written about how students fail, and about how failure affects students, but I wondered how much has been written about failure from the perspective of the teacher. Are we affected when our students fail? Does student failure effect change in our teaching, in our assessment, and in our professional identity? And, from another angle, what are our assumptions about failure, based on our own experiences? Perhaps most importantly, how can we talk to our students, and to our colleagues, about failure? Can we collectively start to reimagine what failure is, what it represents, and how it (should) influence(s) teaching and learning?

Yet, when it comes to failure in the academic context, we have a different understanding, a different regard for the student who fails a test, a course, or a grade. There seems to be a lot written about how students fail, and about how failure affects students, but I wondered how much has been written about failure from the perspective of the teacher. Are we affected when our students fail? Does student failure effect change in our teaching, in our assessment, and in our professional identity? And, from another angle, what are our assumptions about failure, based on our own experiences? Perhaps most importantly, how can we talk to our students, and to our colleagues, about failure? Can we collectively start to reimagine what failure is, what it represents, and how it (should) influence(s) teaching and learning?

In this paper, I want to explore some of those questions, and look at how we rationalize failure in other aspects of life – in video games and driving schools, for instance – yet equate failure with catastrophe and psychological damage in the academic context. I’ll reflect on my own experiences, as a teacher, a student, and a parent, with failure, and (I hope) get some input from other teachers and students on failure in the STEM fields, in high-stakes standardized testing, and at various levels of education. Finally, in a wild attempt to connect this tangent to my dissertation research, I’ll reflect on failure and identity, from both student and teacher – and perhaps, institutional – perspectives.

Suggestions for resources and, in particular, personal input would be very much appreciated. If you think you’d like to share, but aren’t sure where to start, consider these questions for inspiration:

And, of course, if you have other ideas, please share!

For the past three weeks, I’ve been continuing the journal experiment, and yesterday, I took some time to get feedback from the class on their experience. I gave them ten questions to discuss in small groups, then asked the groups to share their responses. I figured that small groups would mean more responses, rather than relying on the more extroverted students, and would open the door to more critical feedback, as no one student had to claim responsibility for a perceived negative comment. I made no notes in class, as I’m trying to avoid using their words directly in my account of the project, but these are my reflections on the general discussion:

small groups, then asked the groups to share their responses. I figured that small groups would mean more responses, rather than relying on the more extroverted students, and would open the door to more critical feedback, as no one student had to claim responsibility for a perceived negative comment. I made no notes in class, as I’m trying to avoid using their words directly in my account of the project, but these are my reflections on the general discussion:

Not a lot of response; people seemed positive, and no one reported that their group complained or discussed doing away with the activity. Lest the lack of response be taken as indicating a lack of participation, let me say that it seemed to me that most groups did genuinely engage in the discussion. I only had ten minutes to give them for the discussion, so it’s certainly possible that they didn’t have enough time to articulate more affective responses, and focussed on more concrete questions.

One group said that the general prompts are good because they can write about anything and even vent a little. They seem to be using the journals as an outlet. On the other hand, another group said they really liked the prompt to think about a passage in the book or to relate themselves to a specific character. My take-away from this is that providing a few prompts is a good idea, since they then can choose specific or general, so I’ll continue to provide three or four writing ideas each session. I will, however, be more conscious of choosing prompts that provide both opportunities. Continue reading “The Notebooks, three weeks in”

I had a sudden flash of inspiration this week, and that flash has turned into a whole laser show.

I’ve been trying out various immediate feedback techniques in class, as described elsewhere on this blog. This semester, I am teaching my Montreal Writers course (you can check out our Facebook page), and our first novel is Gabrielle Roy’s classic The Tin Flute. If you’re not familiar, the novel is set in Montreal, during WWII, and explores the desperate poverty of St-Henri through the story of the increasingly large, increasingly desperate Lacasse family.

In order to provide some way of understanding just what it means to live in real poverty in a place like Montreal, I show the class an NFB documentary called The Things I Cannot Change. The filmmaker followed the Bailey family for three weeks in 1967. Although it’s more than 20 years after The Tin Flute, the circumstances are remarkably similar – the Baileys are a family of nine children, with another on the way; the father is unemployed and, although he waxes eloquent about his opportunities and previous adventures, he fails to find work, and even ends up in an altercation with police.

Prior to the film, I asked students to reflect on what they imagined living in poverty meant in terms of personal identity. Once the film was over, I asked them to write in response to at least two of the following questions:

I collected their responses – a pile of papers, most ripped from spiral-bound notebooks, some larger or smaller than standard, some with viewing notes, and so on. Of course, when I return the pages, there’s a good chance that they will go astray, whether deliberately or accidentally. So my flash of inspiration was this: I went to the stationery store and bought enough Hilroy exercise books for everyone. The pages will be tucked into the notebooks, and when I deliver them, I will suggest that the students affix these pages somewhere in their notebook. Then, for the rest of the semester, I will distribute notebooks at the beginning of each class, and collect them at the end of each class. Students will have time to write at the beginning of class, and again at the end, and between classes, I will read and write in response. Sometimes, my responses will be to the whole class – so, for instance, several students wanted to know whether the Baileys were compensated for their participation (they were, $500). Rather than repeating my response to each student, I’ll bring the answer to class, and/or post it on the Facebook page.

I collected their responses – a pile of papers, most ripped from spiral-bound notebooks, some larger or smaller than standard, some with viewing notes, and so on. Of course, when I return the pages, there’s a good chance that they will go astray, whether deliberately or accidentally. So my flash of inspiration was this: I went to the stationery store and bought enough Hilroy exercise books for everyone. The pages will be tucked into the notebooks, and when I deliver them, I will suggest that the students affix these pages somewhere in their notebook. Then, for the rest of the semester, I will distribute notebooks at the beginning of each class, and collect them at the end of each class. Students will have time to write at the beginning of class, and again at the end, and between classes, I will read and write in response. Sometimes, my responses will be to the whole class – so, for instance, several students wanted to know whether the Baileys were compensated for their participation (they were, $500). Rather than repeating my response to each student, I’ll bring the answer to class, and/or post it on the Facebook page.

My feeling is that there are several benefits to this approach, which is called “double-entry journaling” because both teacher and student are writing in the journal. First, prompts will be used to allow students to explore concepts and texts in class, and their own relationship to those ideas. Their responses will reveal to me any patterns of misconception or misinterpretation, and my feedback will get them used to the idea of receiving regular, non-corrective feedback – I’m even planning to write in red ink, just to show them that red is not to be feared! As an added bonus, I think I’ll get to know their names faster, without having to rely on the attendance list.

I’m compiling a list of writing prompts. So far, I think the first and last question of my original assessment, with rewording to fit specific contexts, are reliable cornerstones of the strategy. I’m also thinking that for opening questions, I can ask them to summarize the main plot points in a reading assignment, or the previous lesson; summarize one passage in the reading that they feel is significant, and explain why; or simply respond to my feedback on their previous response. For the closing reflections, I can ask them to tell me which one thing in the day’s lesson was most unclear to them; to share a personal anecdote related to today’s lesson; to discuss a text or film that they were reminded of by the assigned reading, and so on.

If there are any suggestions you have for prompts, please, PLEASE comment below.

Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for college teachers. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass.

Hampton, S. E., & Morrow, C. (2003). Reflective Journaling and Assessment. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice, 129(4), 186-189. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

Roy, G. (1947). The Tin Flute (H. Josephson, Trans.). New York: Reynal & Hitchcock.

Earlier, I posted about using a new lesson for teaching students about thesis statements. The plan was heavy on interactive feedback, which in turn was something I used more frequently this semester. As we got into planning and drafting the final essay, I came back to the thesis lesson a few times, and made sure to include feedback on their thesis statements when I reviewed their outlines for the essay. I was happy to see that overall, the theses were stronger and clearer, and the final outcome was a batch of pretty well written essays.

At the beginning of each course, as part of my overview and introduction, I ask students to think about what they expect from the course, and what they hope to achieve. I give some space in my course pack for them to record these thoughts, and at the end of the semester, their final assignment is a personal reflection on whether their expectations and goals were met. I also ask them, among other things, to discuss which aspect(s) of the course they found most useful.

Last night, I read the reflections of this semester’s class, and I was thrilled to see that several students discussed the thesis lessons in particular as helpful, not just for our class, but for their writing in other courses. Many discussed the emphasis on writing stages as very useful and, in some cases, a sort of epiphany about writing; but I’ve been using that approach for a while, and I’m used to getting that feedback in their reflections. The thesis lessons were new, however, so I was gratified to get validation of the new tactic.

Of course, the end of my teaching semester is also, more or less, the end of my student semester – I’ve officially finished my first semester of my doctorate. It was a great three months, and I’m excited, still, about moving forward with my research and my writing. So, not a finish, but a pause.

But first, a few days of baking and present wrapping. Happy holidays!

In our doctoral seminar, we’ve been talking a lot about genre and writing strategies. Last night, we experimented with free-writing, or discovery writing, or any other label you’re familiar with. The idea is to write non-stop for a certain period, without backtracking, correcting, planning or pausing.

In our doctoral seminar, we’ve been talking a lot about genre and writing strategies. Last night, we experimented with free-writing, or discovery writing, or any other label you’re familiar with. The idea is to write non-stop for a certain period, without backtracking, correcting, planning or pausing.

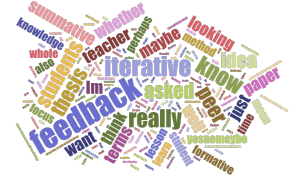

My original intention was to rework my writing from that session, and create a new post (it has been AGES, after all), but then I thought it might be interesting to get feedback (see what I did there) on the brain spurt itself. So, sans editing, this is what I wrote last night:

Continue reading “[working toward] Definition, Direction, and Discourse”