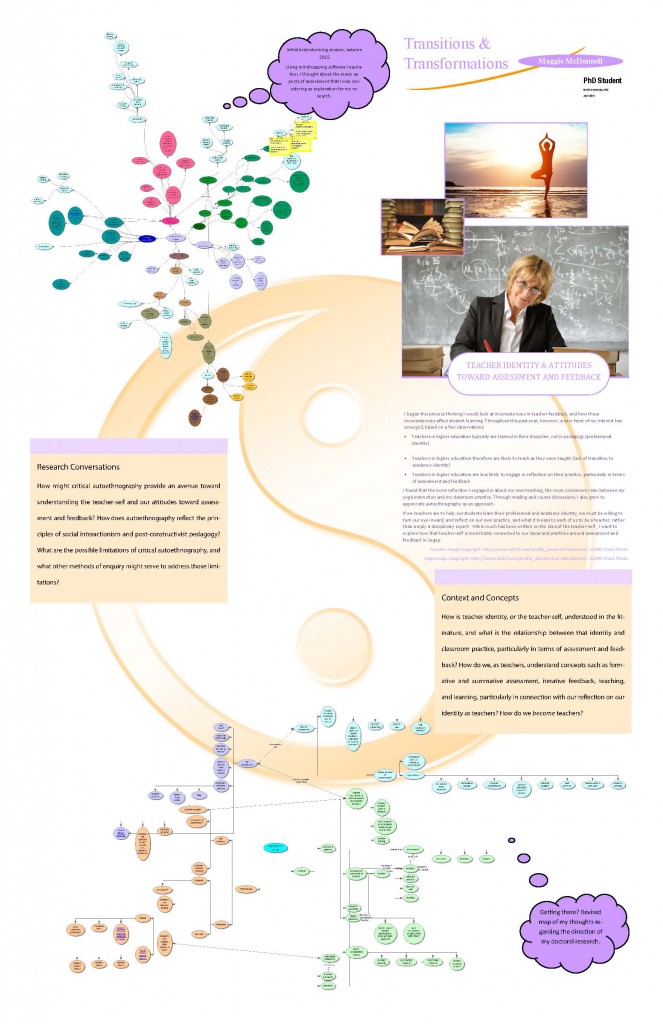

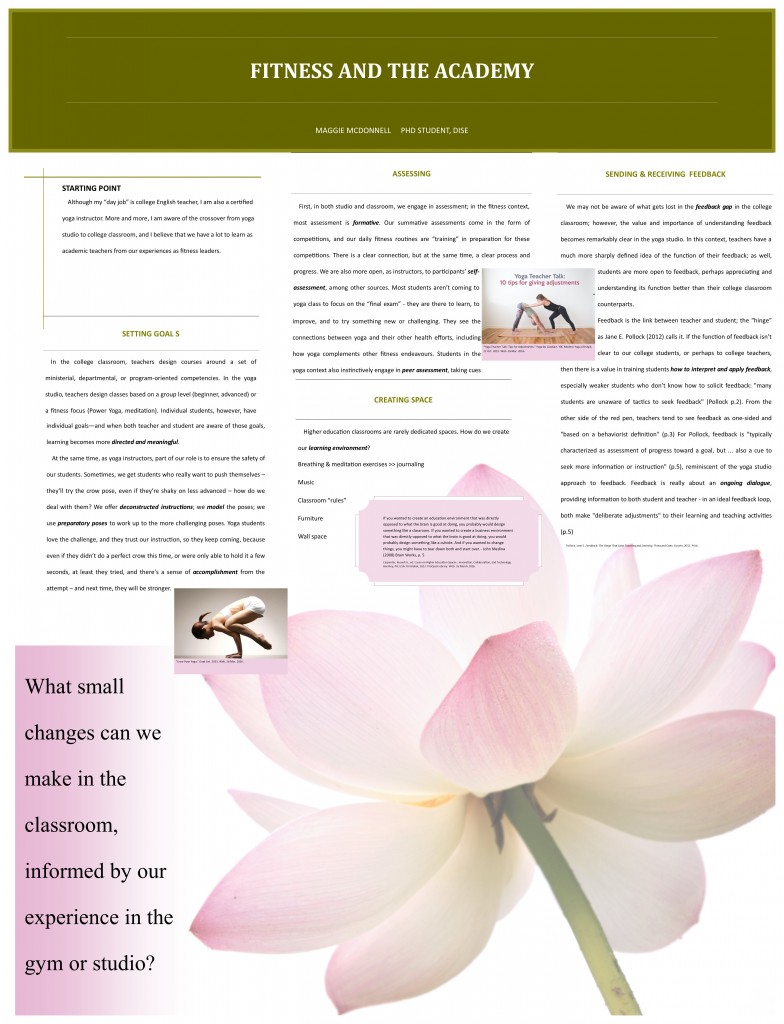

One of the things that yoga has taught me about the academic classroom is not to take for granted that my instructions are clear. Just because I know what I mean – or even if half the class does – doesn’t mean I’ve reached everyone.

In my yoga classes, I do a variation on sun salutations that includes a twisting low lunge. It always astonishes me how many people instinctively twist away from their front knee, into an awkward and unstable twist. 1 It took me months before I realized that I needed to change my cues to reach those people. About half the class got the ‘let’s raise our arms and twist right,’ but in every class, I’d look up to see more than a few in the shaky went-the-wrong-way version, looking at me with distrust in their eyes. They clearly felt something was wrong, but having misinterpreted my cue, they weren’t at all sure how to correct.

Then I started saying ‘let’s twist toward that front knee,’ and they all got it. My revised cue also works for the few who inevitably lead with the left leg when I cue the right, since my cue is no longer based on direction, but on relative position. I think it also helps that the cue references a specific point on the body, so there is no confusion of right/left, with no fixed point.

So, I realized, I need to be willing to reflect on my cues, and be open to changing them, even I think they’re pretty straightforward. We don’t all visualize our bodies the same way, so while I might be generally comfortable with direction-based cues, 2 I have a responsibility to find other ways to lead people through the poses.

I’ve also realized that I need to be open to variations, and not just when I’m offering them. 3 At the end of every class, our final pose is Savasana (the Final Relaxation, or Corpse Pose – and hence one of the few that I only name in Sanskrit). Getting into Savasana is pretty straightforward, and I give a series of cues for coming out of the relaxation after two or three minutes: I ring a tingsha bell, then I say “to come back, let’s start with small movements of the wrists and ankles, then a nice big stretch, and a moment on our sides, in a fetal position, eyes closed… and when we’re ready, let’s use our arms to push up to seated.” It drove me bananas that so many people shifted and fidgeted during the Savasana, and even more bananas when they completely ignored my sequence to come back to Easy Seated Pose for our Namaste. One of my regulars hugs her knees to her chest and rocks herself manically to come straight upright!

But it struck me that my stressing about Savasana was counterproductive. So, rather than insisting on the sequence, I’ve started saying “find any position, laying on the mat, where you can be comfortable and just relax for a few minutes,” instead of insisting on the ‘real’ Corpse Pose. When I ring the tingsha, now I say “let’s take whatever movements we need to come back” and then offer some of the sequence as options. Some people do the whole sequence, some choose one or two of the steps, and my rocking horse still rocks herself back up. I let go of my rigid definition of Savasana, and now we’re all more relaxed.

If I consider both examples – the low twist and the Savasana – it’s clear to me that for the twist, I needed to find a new way to explain, in order to ensure that the pose is safe and stable. For the Savasana, on the other hand, I needed to let go of my vision, and allow people to find their own best expression.

How does this realization – that it’s not them, it’s me – manifest itself in the academic classroom?

Last week, I had my Master’s students work on an exercise in assessment. I gave each group a different colourful image, and instructed them to determine the learning objective, the appropriate and acceptable evidence that the objective has been met, and, using backward design, to decide on the instructional strategies that would get the student to the objective. I thought my instructions were clear enough, yet broad enough to allow for some creativity. The idea was to take the concepts – learning objectives, evidence, criteria for assessment, and backward design – out of the classroom, to make them clearer.

I was initially dismayed, then, when the first two groups that I checked in with showed me their progress and both were using their image as if they were teaching a primary class with the image, rather than teaching someone toward the image. In other words, the lovely photo of the garden, I thought, would inspire a lesson on how to plan and plant a garden; the group with that photo, however, used it to teach children how to identify colours.

My first reaction was to “correct” the groups, and get them to consider the garden as the objective, rather than the tool. But then I stopped myself, and wondered why I needed them to use the photo the way I thought it should be used. Would they not get the concepts if they changed the function of the photo? Would my exercise somehow not work? Would they be unable to present an objective, an assessment, and a learning plan? The answer to all of these questions was ‘no,’ of course. So rather than correct the groups, I discussed their ideas with them, and let them get on with their work.

In the end, about half the groups worked with their photos as tools, rather than as objectives. Each group presented to the class, and gave feedback to each other, and there were no problems at all – most groups began with “we chose to think of the photo as…” and we all accepted each group’s approach.

In future iterations of the course, I plan to use this exercise again, but I’ll model my idea of how to use the photo. I still think it’s valuable to think about assessment outside of the classroom context (as my yoga crossovers demonstrate!), so I’ll adjust my instructions to guide students in that direction – but I won’t get bogged down in “why don’t they get it?” frustration. I need to learn to recognize the “why don’t they get it?” reaction as a cue for me, to reflect on what I’m saying, and how, and whether, ultimately, different interpretations are problematic.

Is this a twist, or a Savasana?

- yes, it’s certainly doable, but for the level I teach, it’s not a comfortable pose ↩

- and honestly, I’m just as likely to go left when someone says right, especially if I’m teaching and being the mirror. I have to cue Eagle very, very slowly. ↩

- Because I teach “all-level” classes, I tend to offer several options for poses as we go along. So, for instance, I might cue Downward Dog, but give the option of Child’s Pose as an alternative. ↩