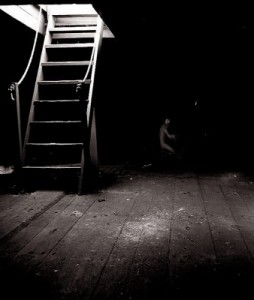

Since it’s October, it seems fitting to write about my ghost student.

Last autumn, Jennet was one of only nine students registered in my third-semester English for Liberal Arts course. For the first few classes, only eight students attended; Jennet was nowhere to be seen. I assumed she would eventually drop the course – it’s not uncommon in this program for students to transfer to another program or college after their second semester.

But then she appeared.

About three weeks into the semester, we were getting into our feminist readings of Frankenstein, and settling into a nice, intimate group dynamic.

I was really enjoying the course – with only eight students (or so I thought), and a teaching intern, I could experiment with pedagogical activities. We had a great time doing debates, four against four, for instance. The tiny class size did mean other activities, such as the group presentations, required some finessing, but generally, this was a fun class to teach. We had a great group vibe, too, not least because the eight students had already been through two semesters together, so I didn’t have to do any community building.

Then she appeared.

Jennet showed up one day, loud and energetic, chatting with her classmates. She did not bother to introduce herself (perhaps she assumed, justifiably, that I would know the one person in a group of nine who hadn’t been there yet) or explain her absences. She contributed to class discussion, albeit not always from a place of understanding, since she had not been there for previous discussions, nor was she up to date with reading. But I felt odd about her presence—like she was more disruptive than she actually was, just by being there.

Then she disappeared.

Jennet did not return to class the next day. In fact, the next time I saw her was in my office, for the mandatory essay conference. These conferences are based on in-class writing: stage one is the thesis planning, with feedback, then the outline, with feedback, then the in-class draft, with feedback. Before writing the final version of their paper, students must meet with me to discuss the three stages and the feedback I’ve provided, and talk about what they plan to do with the final version.

She appeared.

She had not been in class for her thesis planning, nor for the outline, nor for the draft. I was, frankly, taken aback when she appeared in my door (at least in part because I genuinely wasn’t sure who she was, having only met her once before). She sat down and handed me a typed draft of an essay that did not address the topic assigned. I told her this, and said that if she handed this essay in, she would fail. I offered her a deal: take an extra week, but send me an outline within two days, with a plan for an essay that answers the questions asked in the assignment. She agreed.

Then she disappeared.

She did not hand in an outline, nor did she hand in an essay. We were already past the deadline to drop courses, but what more could I do? I did not follow up with her – although I did ask one of her classmates about her chronic absences. He assured me that the problem wasn’t me (I didn’t really think it was, given how little we’d actually interacted), but rather some kind of self-defeating habit of not showing up. So I left it alone, and the semester continued, back to our now-established good groove.

Then she appeared.

She showed up once more that semester—her second ever classroom appearance—during oneof our debate classes, which was unsettling, given that we had been working with two teams of four. One of the teams invited her to join them, and she seemed to work well with the group. Again, though, I felt perturbed by her reappearance, not to mention puzzled: she had already missed two of the three essays, several reading quizzes, the group presentation, and there was, mathematically, no way she could pass the course. I expected her to come to my office or send me an email, asking how she might “make up” all the missed work. I rehearsed my response—but no such request came.

She disappeared.

Jennet never dropped my class, but she never submitted any work, either. Thanks to one reading quiz and her participation in one debate, her final grade for the course was 1.2% (note the decimal. One POINT two percent).

Then she reappeared.

Imagine my surprise when Jennet appeared on my class list for this semester, for the same course. This is a program course, required for Liberal Arts students—and apparently, Jennet is still among them. Three weeks into the semester, however, Jennet still had not attended a class. I contacted the program chair, who agreed that she was likely to fail and added that she is currently on academic probation, meaning that failing my class (or any other) would result in her expulsion from the program.

Then she reappeared.

The following week, Jennet was in class. This time, she was subdued, presumably because this year, she doesn’t know her classmates, since their cohort (a group of 23) started the year after hers did. She made a few contributions to the discussion—good ones, even—and approached me at the end of the class to ask if she could meet with me to discuss what she had missed. I agreed. I introduced her to a group who are scheduled to present later in the term, and asked if they would consider including her in their group. They agreed.

Then she disappeared.

Jennet did not attend the next class, or the next week. The drop deadline was approaching, so I sent her a message and reminded her that failing my class would affect her standing in the program, so she should consider dropping my class and discussing her options with the program chair.

She did not drop my course. The drop deadline came and went, but her name remained on my list, even though her body never came back to class. I advised her presentation group to assume that she would not be working with them after all. In the meantime, we had done the thesis planning, the essay outline, and the in-class draft. I set up an online appointment calendar for the essay conference—and she made an appointment.

She did not appear.

And then she did appear.

The week after the essay conferences, she came to class. Once again, she approached me, and asked if we could meet. We met on Tuesday this week; she did not have any work to show me, but she wanted to explain the many, many reasons she is almost always unable to attend class. I pointed out that so far, she has been to two classes. She told me that’s more than she’s attended any of her other courses. I’m flattered, obviously, but concerned. I asked why she’s in Liberal Arts? What does she want to do?

Corporate Law.

Oh dear. Time for some straight talk. Corporate Law is a very, very long shot for someone with her transcript. I don’t even bother pointing out how unlikely it is that she’ll get academic referees. I ask her if there’s a Plan B, and she tells me that she’s wanted to be a lawyer since she was four. I tell her she needs to start entertaining other options. I tell her she needs to get her sh*t together (and I’m not paraphrasing). Honestly, I expected her to nod and look abashed and swear to do better and then disappear.

But she came back.

She’s in class on Thursday, with her thesis and outline. The essay is due this coming Tuesday, so I tell her that I will accept her outline, and give her feedback, but she needs to come to my office Friday afternoon and collect it.

She appears.

Yesterday afternoon, she collected her outline, discussed her feedback, and promised to submit an essay.

I wonder if she has any idea how much thought I have put into her case. Does she think that I think about her at all? Or does she assume that in higher ed, we profs just don’t care about our students the way our K12 counterparts do? There are no calls or notes going home to parents, so perhaps the impression is that it’s sink-or-swim, and we’re not lifeguards. Certainly, there is only so much I can do—last year, I didn’t do much at all, frankly, but then, neither did she. This year, she is reaching out, however sporadically, and I’m trying to keep the life buoy within reach.

When I saw her name on my class list in August, and when I wrote to the program chair, I had firm resolve that if and when she appeared, I would exorcise her. No second chances. I don’t have time or space in my class to indulge this inexplicable behavior. I have a new group, with their own dynamic, and I don’t want to disrupt them for the sake of one prodigal classmate.

But I caved. She appeared, and I invited her in. She disappeared, and I rolled my eyes. She reappeared, and I met her halfway. She vanished, and then came back.

I think I need a proton pack.